In the previous article, I briefly dissected the common arguments

against the basic historicity of the Exodus tradition. In this article I

will present some of the evidence in its favor, though I will leave many

specific details for the succeeding articles in this series.

1. The Unlikelihood of Invention

One reason many, if not most, scholars hold that the Exodus story

has a historical core is that it is otherwise difficult to explain why the

Israelites would have invented a story that portrays their national origins as

lowly slaves laboring on Egyptian building projects. As Kitchen frames it, “If there never

was an escape from Egyptian servitude by any of Israel’s ancestors, why on

earth invent such a tale about such humiliating origins?...That question has

been posed enough, and the sheer mass and variety of postevent references gives

it sharp point.”[1]

By “postevent references,” Kitchen is referring to the fact that

references to the Exodus occur throughout the different biblical sources

including even the earliest Hebrew texts: J, E, P, and D (the different sources

of the Torah, according to the Documentary Hypothesis long held by biblical

scholars), the Psalms, the different prophets, and so on. This suggests that the slavery in Egypt was

widely accepted by the Israelites as their historical national origin, and not

merely a myth invented by a few writers or a single party.

2. Semitic Slave Labor

The opening chapter of Exodus describes the slave labor the

Israelites were forced into:

Therefore they

set taskmasters over them to oppress them with forced labor. They built supply

cities, Pithom and Rameses, for Pharaoh. (Exod. 1:11)

The Egyptians

became ruthless in imposing tasks on the Israelites, and made their lives

bitter with hard service in mortar and brick and in every kind of field labor.

(Exod. 1:13-14)

The use of Semitic people for slave labor is a well-known

phenomenon of ancient Egypt beginning in the New Kingdom period, i.e. after

around 1540 BCE. This means

that the notion that the Israelites were slaves in Egypt forced to labor in

construction projects has a credible historical backdrop.

The Book of Exodus even gives specific details about the nature of

this slave labor:

Thus says

Pharaoh, “I will not give you straw. Go and get straw yourselves, wherever you

can find it; but your work will not be lessened in the least.” ’ So the people

scattered throughout the land of Egypt, to gather stubble for straw. The

taskmasters were urgent, saying, ‘Complete your work, the same daily assignment

as when you were given straw.’ And the supervisors of the Israelites, whom

Pharaoh’s taskmasters had set over them, were beaten, and were asked, ‘Why did

you not finish the required quantity of bricks yesterday and today, as you did

before?’ (Exod. 5:1-14)

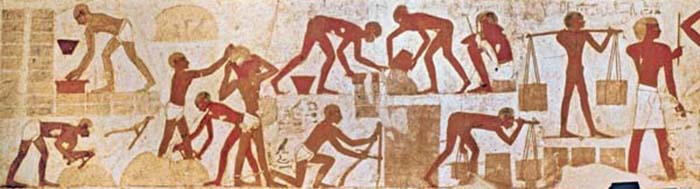

Remarkably, all of the details of this description are confirmed

by the a relief on a wall of the Tomb Chapel of the vizier Rekhmire (c.

1450). The painting shows

Semites and Nubians building the Temple of Amun at Karnak in Thebes, gathering

straw and measuring the building materials to meet a specified daily quota:

3. City Names and Descriptions

The Book of Exodus names specific cities where it locates the

Israelites:

“Therefore

they set taskmasters over them to oppress them with forced labor. They built

supply cities, Pithom and Rameses, for Pharaoh.” (Exod. 1:11)

“Pithom” is now identified as Per-Atum in the modern Tell

el-Mashkuta. “Rameses” is

identified as Pi-Ramesses, built into a large city by Ramesses II (r. c.

1279-1213 BCE) to be his capital in the East Nile Delta. (This is one of the

evidences, as we will see, for Ramesses II being the pharaoh of the

Exodus.) Pi-Ramesses was

indeed a “supply city” as the above quote from Exodus states. It had workshops and storage magazines

for palaces and temples. As Kitchen[2]

and Hoffmeier[3]

point out, because the city was abandoned in the 1130s BCE, it could not have

been known to the authors of the Book of Exodus if they were writing a made-up

story many centuries later. They could

only have received it as an authentic detail preserved in the memory of an

actual historical Exodus from Egypt.

Additionally, the biblical text

states that the Hebrews required

two days to travel from Rameses to Succoth to Etham (Exod. 12:37; 13:20; Num.

33:5-8). The Papyrus

Anastasi V also gives the same time frame with reference to two escaped slaves

who took the same route.[4]

4. Israelite People Names

Another reason for believing that the Exodus story has a

historical core is that many Israelite names appear to be of Egyptian origin:

a relatively

large number of Egyptian personal names are found within the tribe of Levi

(e.g., Moses, Aaron, Miriam, Merari, Putiel, Phinehas, Hophni). There is

therefore a basis to surmise that ancestors of some Israelites, and

particularly those associated with the priestly tribe, came out of Egypt.[5]

This is, of course, unlikely on the assumption that the Israelites

emerged completely indigenously in Canaan.

5. Environmental Descriptions of the Sinai

The descriptions of the Israelites’ sojourn in the Sinai Peninsula

found in the books of Exodus and Numbers are strikingly consonant with its

actual natural conditions. This

includes the mention of the quails and their flight patterns, the miracle of

the water from the rocks, salt-tolerant reed marshes, and even geographical

descriptions, such as the description of the route the Israelites took down the

southern coast of the peninsula (see point 1 in the previous article). We will mention these in a later

article.

We see from this that the details found in the biblical

descriptions of the Exodus and Wandering could not have reasonably been

produced by scribes writing in Palestine or Babylon many centuries after the

alleged events. The details

are accurate and could only have been passed down from actual experiences in

Egypt and the Sinai Peninsula, particularly towards the end of the New Kingdom

period.

No comments:

Post a Comment